The 1972 Building Workers’ Strike

The building workers’ strike of 1972 was one of the most important strikes in Britain after the Second World War. It involved hundreds of thousands of workers from many different building trades. They came together to demand better pay, safer working conditions, and shorter hours. The strike showed that even in a difficult industry to organise, workers could take action and win major gains.

Background

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Britain had a big construction boom. New homes, schools, offices and roads were being built. But conditions for building workers were often poor. Many were on what was called “the lump.” This meant they were classed as self-employed and paid in cash, with no holiday pay, sick pay, or job security. Safety on sites was often bad and accidents were common.

Several unions represented workers, including UCATT (Union of Construction, Allied Trades and Technicians) and the Transport and General Workers’ Union. But the industry was very split up, with lots of small sites and short-term contracts. This made it hard for unions to organise. A group called the Building Workers’ Charter began to campaign for a national strike to win better pay and conditions.

The Start of the Strike

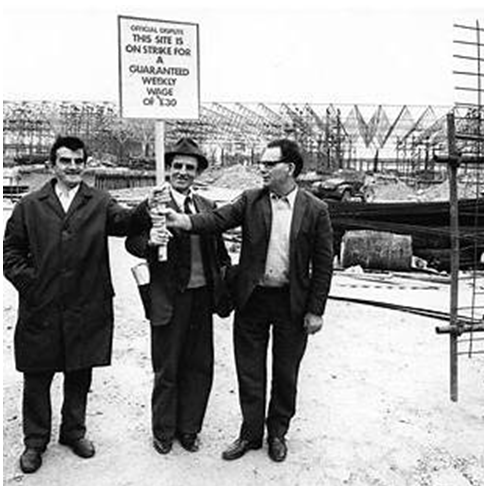

In early 1972, the unions put in a claim for a minimum wage of £30 per week, a 35-hour week, and an end to the lump system. The employers rejected this claim. In May, selective strikes began on major sites in big cities. As the strike grew, workers started using “flying pickets.” These were groups who travelled from site to site to persuade other workers to stop work and join the strike.

By August, the strike had spread across the country. At its height, around 200,000 workers on more than 7,000 sites were involved. Most big construction projects were shut down. This put heavy pressure on the employers to agree to a deal.

The Settlement

On 14 September 1972, after about 12 weeks of action, the strike ended. The settlement gave skilled workers an extra £6 per week and labourers £5. This was the largest pay rise in the history of the industry. However, the demand for a 35-hour week was not met, and the lump system was not abolished. Many workers felt proud of what they had won, but also disappointed that some of their biggest aims were not achieved.

Consequences and the Shrewsbury 24

After the strike, employers and the government moved against union activists. Flying picketing was blamed for “intimidation,” and 24 workers were arrested and put on trial. These men became known as the Shrewsbury 24. They were accused of conspiracy and jailed. Many people saw this as an attack on the right to strike. It took almost 50 years for these convictions to be overturned, in 2021.

Blacklisting also became common after the strike. Many activists found it hard to get work because their names were secretly shared between employers. This weakened union organisation on building sites in the years that followed.

Why It Was Important

The 1972 strike showed the power of solidarity. It proved that even in a fragmented industry, workers could unite and win major pay rises. It inspired other groups of workers, such as miners and dockers, to take action in the same period. However, it also showed how employers and the state could try to punish union activists and limit the gains of a strike.

Many of the problems faced by building workers in 1972 still exist today: insecure contracts, safety risks, and pressure on pay. The strike remains an important example of what workers can achieve through collective action, but also a warning of how hard it can be to hold onto those gains.