Keeping it in the family, is plastering in the blood?

The family run N & E Woodhouse Plastering Contractors have been established more than 50 years and and has seen four generations of plasterers learning new skills and passing down old ones. Although much of our work is with modern plasters our experience and heritage has us well placed to carry out work on some of the older building in and around York.

I have this feeling that, for some reason, plastering seems to run in the family more than any of the other trades. Maybe it’s just my own personal experience?

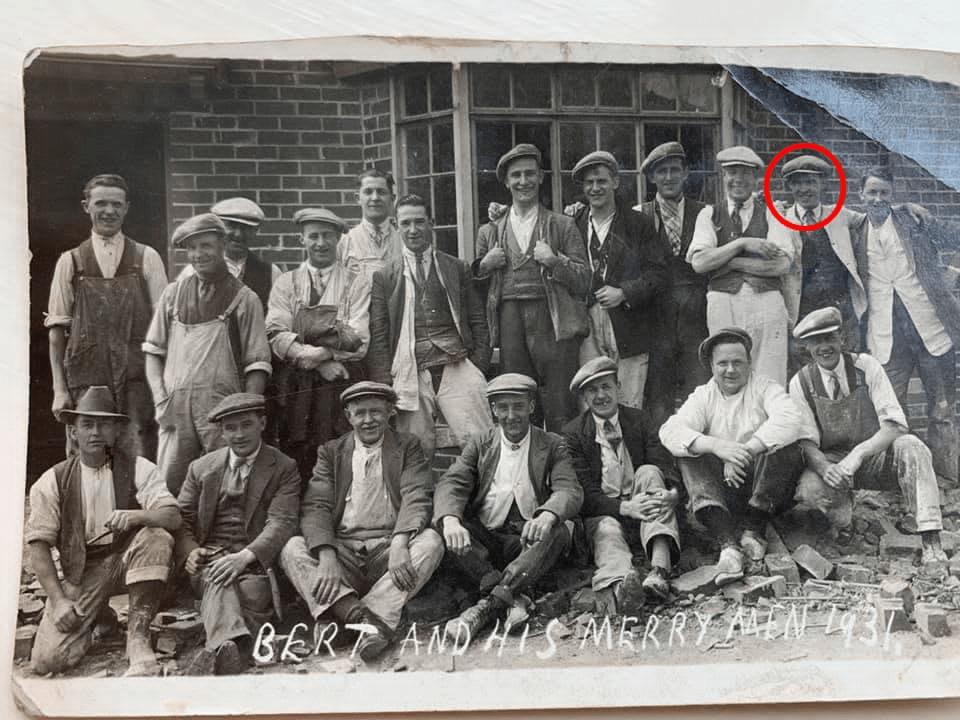

My grandfather, Norman Woodhouse, was engaged as an apprentice plasterer by the family firm, Taylors, in Doncaster back in the 1930s. His father before him had been a bricklayer in the pits, walling up abandoned seams. And, as they say, a bricklayer is only a plasterer with no brains, right? Those pits weren’t for him.

Norman was best mates with “Nip” Taylor, the boss’s son. Work in Doncaster had slowed, and Mr. Taylor, knowing there was work in York, asked his son to head over there and set up a branch of the parent company. Off he went, taking his mate—newly married Norman—with him. The Woodhouses found a one-up, one-down terraced house with a standpipe in the courtyard next to the communal toilets. It wasn’t much, but it was a start, and there was plenty of work. York had three huge council estates being built and acres of new housing to go at.

Norman and his wife, Alice, soon found themselves in one of those council houses and started a family. The youngest, Ernie, decided to follow his dad into the plastering trade and started an apprenticeship with Birch’s, one of the big construction companies in York. His first day on the job was New Year’s Day, repairing cornicing at the grand Assembly Rooms—not exactly what he’d been expecting.

National Service was still a thing back then, but his apprenticeship meant his start was deferred until he had finished his time. Even so, he still caught the tail end of conscription and was signed up in its final years.

Two years later, he returned home with a different outlook on life. His best mate, Terry Smith, was plastering with his own father at the time, and the two of them figured they could find better work, more money, and—let’s be honest—more freedom away from the family home and out of York. They set off, working their way around the country, eventually finding themselves in Bracknell, working on the new Met Office building. We’d only just started taking weather forecasting seriously during the war, and it was now becoming a major pursuit.

Eventually, they returned to York, their wild oats sown, and settled down—there was plenty of work, and they had girlfriends. Terry set up a small company of his own, and Ernie asked his dad, Norman, if they might do the same. Norman was still with the Taylor family, but they took the chance. They secured a contract to start right after Christmas. Things were looking exciting.

Unfortunately, that Christmas was in 1962—the year of the “Big Freeze.” Nobody was working. Ten weeks of snowfall and freezing temperatures brought the country to a standstill. Ernie, however, found work at York University, which was just being built around Heslington Hall. The hall had a huge cellar, which they kept above freezing using coke braziers—probably the equivalent of smoking 80 cigarettes a day, but it was work.

To make things even more interesting, Ernie became a father that January—Mark (me) had joined the Woodhouse family. So, the work was welcome. Nip Taylor had asked Norman to stay for an extra month or two to finish their work, but by the time spring arrived and the weather cleared, they were officially N & E Woodhouse, Plastering Contractors.

As time went on, they engaged another plasterer, Dave Smith—Terry’s father. A West Yorkshire lad, he had similarly gravitated to York after the war in search of work. So, having left the Taylor family business, father and son had set up on their own, taking on the father of their mate. Things were working out. It was the 1970s, there was plenty of work, and they had a good set of lads.

Then Dave asked if there might be an opening for his own son, Phil. And so the intertwined plastering family continued. Work was good, squash became popular, and there was well-paid work plastering squash courts all over the country.

By the 1980s, I was leaving school. Guess where I ended up? Two Woodhouses, two Smiths, and a labourer.

Years later, I had my own sons, and my dad, Ernie, retired. Then, in the early 2000s, my eldest son, Dominic, was leaving school and looking for work. Yeah, you guessed it—plastering.

Ernie’s turning 90 this year. He’s kept his tools. Just last week, his mate needed a reveal plastering after some window installers had left it rough. I think he jumped at the chance to relive his glory days—just like an old retired footballer who can’t walk past a ball without flicking it up and volleying it.

I’ve got five years left until I can collect my state pension. I wonder if I’ll still have my tools when I hit 90? I probably will, and I’d do it happily—knowing that Dom’s son, Milo, who’s six, has already told his dad he wants to be a plasterer when he grows up.

Perhaps he’ll carry on the tradition of the Taylor, Smith, and Woodhouse families.

Is it in the blood?